Gospel: Luke 15:11-32

In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

My dear brothers and sisters,

For the past two Sundays we have been meditating on two tax collectors. The first, Zacchaeus the short tax-collector that proved himself to be tall in the spiritual life through repentance; and the second tax collector, the Publican of the parable we heard last week who saved himself through seven words – “God be merciful to me a sinner”. Today we come to this second Sunday of this Pre-lenten season and hear of another beautiful parable of our Lord again from St Luke’s Gospel – the Parable of the Prodigal Son. Through this parable, our Lord continues to teach us about the fathomless depth of His mercy and love for His sinful, fallen and often thoroughly messed up creatures. This revelation is at the very heart of what makes the Gospel the Gospel, the good news, the joyous and gladsome news that God has come not to condemn, to judge or to destroy, but rather to seek out, to save and heal that which was lost, that which was sick, and to bring us back to the Paradise that we left. To help us understand this parable, let us turn to St Gregory Palamas, that great father and pillar of Orthodoxy who we will commemorate soon on the Second Sunday of Great Lent.

And he said, A certain man had two sons:

As St Gregory says, ‘in this parable the Lord calls Himself a man. There is nothing strange in this. If He truly became Man for our salvation, it is not at all strange if He presents Himself as one particular man for our benefit’. More specifically we can identify this ‘certain man’ of the parable with the Divine Person of the Father. We will meet the Person of the Son, later on in the parable. With regards to his two sons, St Gregory interprets this as indicating that after the Fall, mankind became divided and split within itself as he says, ‘the distinction between good and evil gathered many people into two’. We can all fully empathise with this, our nature is single, yet our will can tend towards both good and evil. Sometimes we want and fully intend to do good, yet find ourselves, despite ourselves, slipping and sliding into sin. This reminds us of St Paul’s Word in his epistle to the Romans, when he talks about the strange, schizophrenic selfhood of the sinner: ‘I do that I would not, it is no more I that do it, but sin that dwelleth in me’.

And the younger of them said to his father, Father, give me the portion of goods that falleth to me.

In the parable we are then introduced to the two sons as divided in age, one older and one younger. St Gregory identifies how appropriate it is that the younger son asks this question, since the question is such ‘a childish and foolish request’. Not only, we can say is the request itself childish, but the way in which he says it has a strikingly childish impudence about it. He doesn’t beg or beseech his father to give him his inheritance with meekness and entreaty. He just demands it – now – as his birthright and in the imperative – ‘give me the portion of goods that falleth to me’. He demands his inheritance, indeed, whilst his father is still living. What an appalling, arrogant and hurtful attitude this is. As St Gregory says, ‘By what law and which justice are fathers in debt to their children? Quite the opposite: children are in debt to their fathers, as nature proves, for they own their existence to them.’

And he divided unto them his living.

Despite the ingratitude and insolence of the younger son’s request, the father of the Parable doesn’t argue, but with meekness of heart, fully respects the freedom of his son. St Gregory also notices another interesting thing, that the Father, ‘needs nothing for himself … Being God, He has no need of our good things. As David says (Ps 15:2). So he divided his living, which means the whole world, between these two sons’. In this way we can see and marvel at just how much God respects our individual choices and freedom. Whilst the younger son demands, the father doesn’t demand, he just gives. As St Gregory adds – ‘God has divided the whole creation equally to all, offering it to each to use as he pleases’.

And not many days after the younger son gathered all together, and took his journey into a far country, and there wasted his substance with riotous living.

Again, St Gregory homes in on another detail which I certainly had missed the significance of. ‘Why’, St Gregory asks, ‘did he not set off at once instead of a few days after? Again the answer for this is the sly, diabolical and cunning way in which satan works. As St Gregory explains – ‘The evil prompter, the devil, does not simultaneously suggest to us that we should do what we like and that we should sin. Instead he cunningly beguiles us little by little …’. It thus took a few days for the devil to do his work, to justify and tempt the younger son to resolve what he should do and to voluntarily leave his father’s house, his true home and where he is protected by the father, and instead travel away from home into evil and sin.

And when he had spent all, there arose a mighty famine in that land; and he began to be in want. And he went and joined himself to a citizen of that country; and he sent him into his fields to feed swine.

So the younger son empties himself of his virtue, empties himself of his prudence, which St Gregory describes as ‘the wealth of the mind’ and he disperses and wastes what he has been given. ‘Whenever we open the door to the passions, immediately it is dispersed, wandering continually among fleshly and earthly things, all kinds of pleasures and passionate thoughts about them.’ His right reason and understanding had been overwhelmed and dispersed into the passions. However, this great exodus of the younger son, this exciting new chapter of his life, one of independence and freedom from his father that the devil had tempted him into has rapidly turned into an unmitigated disaster, a living nightmare. He runs out of money and a famine falls upon the earth and ‘he began to be in want’. As St Gregory asks, ‘Who are the citizens and rulers of that country far from God? The demons, of course …’ Again, we can see the lack of mercy, the lack of tenderness in the demonic citizens. They rather cruelly set him straight to work, straight out to the fields ‘to feed swine’. And why is it that he is sent to feed the pigs? St Gregory answers – ‘The life of pigs, because of its extreme filthiness, is symbolic of all the passions. Those who wallow in the mire of the passions are the pigs, of which the younger son was put in charge, as surpassing them all in self-indulgence.

And he would fain have filled his belly with the husks that the swine did eat: and no man gave unto him.

As if he couldn’t have fallen any lower, he even starts to envy the food which the pigs ate. St Gregory interprets his inability ‘to eat his fill of the husks the pigs ate, meaning that he could not find satisfaction for his desires’. Again, there is something about the nature of sinful desire that entails it cannot be satisfied but rather restlessly and relentlessly seeks more and more. He is in real famine, one that is spiritual as it is material.

And when he came to himself, he said, How many hired servants of my father’s have bread enough and to spare, and I perish with hunger!

Then we come to the central turning point of the whole parable. The moment of critical realization when he comes to himself, he attains to a level of self-realisation and self-understanding. He had begun to regain some of the substance, the insight, the prudence which he had dispersed and frittered away.

I will arise and go to my father, and will say unto him, Father, I have sinned against heaven, and before thee,

St Gregory says that it is this line of the parable which indicates that the man was indeed the Person of the Father as we identified at the beginning. As he says – ‘How could this son have sinned against heaven unless his father was in heaven?’.

And am no more worthy to be called thy son: make me as one of thy hired servants.

The impudent son who could speak with such meanness, such arrogance and disrespect to his father at the start of the parable, has been humbled by suffering, and understands how sinfully and disgracefully he has behaved. In this rather sweet scene where far away from home he rehearses what he will say, we can see the life starting to return back into him.

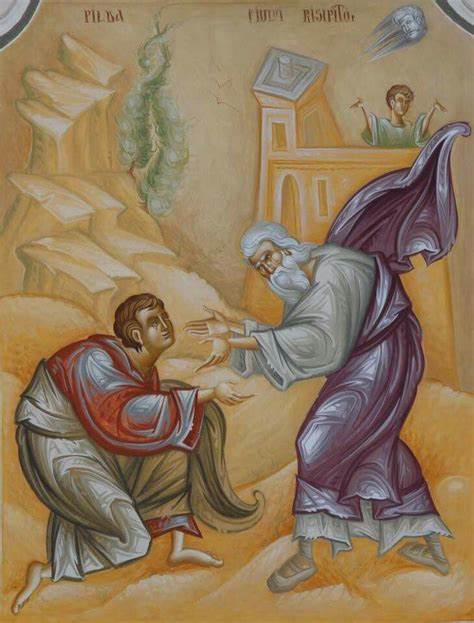

And he arose, and came to his father. But when he was yet a great way off, his father saw him, and had compassion, and ran, and fell on his neck, and kissed him.

So often in the spiritual life we can be haunted by false images of God. The God who hates sinners. The God of Infinite and inscrutable Justice. The God whose Righteousness annihilates and burns us up. Sadly, for many people, it is such false images and understandings of God, that keeps them from coming to Church. Yet, more often than not, this image of God is not God at all, but rather comes to us from the evil one, the Deceiver and Slanderer. If we ever want a true image of God’s love for us, I don’t think that we can do much better than this image of the Father patiently waiting for us to return and then even when we were a great way off having compassion, running towards us and casting himself upon our neck and kissing us. What a stunningly beautiful and perfect verbal ikon of the love of God for us – for you and for me. Note that he doesn’t even wait for one word of apology before running. Even when we are a long way off, He is already running towards us with his arms wide open. This is our God. The True God. The God revealed and incarnated in the Gospel, in the Life of our Lord Jesus Christ.

And the son said unto him, Father, I have sinned against heaven, and in thy sight, and am no more worthy to be called thy son. But the father said to his servants, Bring forth the best robe, and put it on him; and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet:

St Gregory says, ‘The Father of Mercies came down to meet him. He embraced him and ordered his servants, namely the priests, to put on him the best robe, sonship, in which he had been clothed before through holy baptism …’.

And bring hither the fatted calf, and kill it; and let us eat, and be merry:

And who is the fatted calf? St Gregory answers: ‘The calf is the Lord Himself who is led out from the hidden place of divinity, from the heavenly Throne set above all things. Having appeared on earth as a man, He is slain like a fatted calf for us sinners, that is, He is offered to us as bread to eat.

For this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found. And they began to be merry.

As St Gregory says: ‘God shares his joy and celebration over these events with His saints, making our ways His own, and His extreme love for mankind, and saying, ‘Come, let us eat and be merry’.

Now his elder son was in the field: and as he came and drew nigh to the house, he heard musick and dancing. And he called one of the servants, and asked what these things meant.

And he said unto him, Thy brother is come; and thy father hath killed the fatted calf, because he hath received him safe and sound. And he was angry, and would not go in:

The whole of the parable so far has been exclusively concerned with the exploits of the younger son. It is easy to think of the older son, as the “good one”, the perfect, model son in contrast to the profligate and prodigal younger son. However, in his reaction to his brother’s return, we can see that he also is not free of the passions. Let us first pause to consider who exactly this older brother, this older son represents. In St Gregory’s homily he asks us to recall the reaction of many of the Jews in the Gospels: ‘Remember the Jews who were angry when the Gentiles were called, the scribes and Pharisees who were scandalized when the Lord accepted sinners and ate with them’.

therefore came his father out, and intreated him.

Yet again, what do we see but the long-suffering love of the Father who doesn’t destroy us or fly off in a rage, but again patiently goes out to us when we are so unworthy of such condescension.

And he answering said to his father, Lo, these many years do I serve thee, neither transgressed I at any time thy commandment: and yet thou never gavest me a kid, that I might make merry with my friends: But as soon as this thy son was come, which hath devoured thy living with harlots, thou hast killed for him the fatted calf.

St Gregory interprets this again rather childish complaint of the elder son, as the complaint of Israel for the fact that the Son of God, the Messiah did not come to them earlier, at a time of their choosing. As St Gregory says- ‘But he did not come at that time, and when He did come, He came not to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance, and above all, to be crucified for them, taking away the sin of the world’.

And he said unto him, Son, thou art ever with me, and all that I have is thine. It was meet that we should make merry, and be glad: for this thy brother was dead, and is alive again; and was lost, and is found.

There is this stubborn hardness of heart in the chest of the older son. A catastrophic loss of joy and rejoicing. A lack of appreciation of what he does have and what he has been given. Ironically, it was only when the younger son left home that he realized exactly what he had been given. And this is why God loves the sinner who repents. But see again, what incredible restraint, what love and patience there is in the father’s response to his priggish and self-righteous son.

Dear father, brothers and sisters, let us use this Lent to wake up, and come back to ourselves and in so doing we will see that the God we feared, and maybe had fled from, has been long waiting for us and is running to embrace us and kiss us and bring us back home.

Amen.