Gospel [Matt. 18:23-35 (§77); John 15:17-16:2 (§52)]

In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

Dear father, brothers and sisters: Spraznecom!

In today’s Resurrectional Gospel we leave the miracles, exorcisms and healings, the signs and wonders which we have encountered in our readings these past few weeks and today are given one of the starkest and most striking parables of the whole Gospel. Our parable was prompted, by Peter’s question to the Lord a few verses earlier where he asks – ‘Lord how oft shall my brother sin against me, and I forgive me, till seven times?’ Let us interpret this powerful parable of our Lord and also explore together how this parable relates to the wondrous event of the Transfiguration whose afterfeast we are now in? Again, as our guide we shall turn to St John Chrysostom’s Homily on this same parable and see what Golden insights the Goldenmouthed can provide to our Lord’s words.

The parable starts with the image of a King taking account of His servants debts, the first of which owed him 10, 000 talents. This is a large sum of money, but because the currency is unfamiliar to us it is difficult for us to grasp exactly how big this is. In the Old Testament the word “talent” appears when describing how much gold the Israelites used to build the tabernacle. It was a unit of measurement for weighing precious metals like silver and gold and weighed about 75 pounds. The Israelites used 29 talents of gold in the construction of their tabernacle. In the New Testament the word meant something different. From the Greek word tálanton, it was a large monetary measurement equal to 6,000 drachmas or denarii, the Greek and Roman silver coins. It was the largest unit of currency at that time. The denarius was a standard silver Roman coin and equal to a day’s wages. So, if one denarius was what a man like the ungrateful servant could earn in a day, he would need to work 6,000 days to earn one talent. Ten thousand talents would equal 60 million denarii or 60 million days of work. Although my maths is ropey, I make that about 164 years of continuous labour. Thus this debt that the King’s servant owed was not just a large amount of money, it was an utterly unattainable sum of money which would be impossible for him to pay.

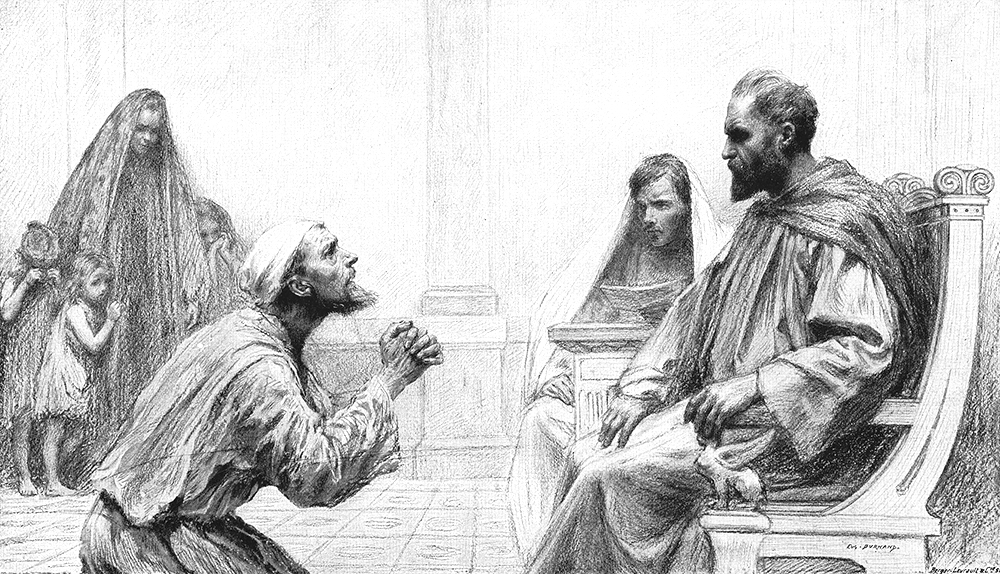

In light of this, it is therefore not surprising that the King, sees the impossibility of the debt ever being repaid and says that the man should be ‘sold, and his wife, and children, and all that he had, and payment to be made.’ This would certainly be the normal, worldly way of doing things. The servant had been grossly incompetent in allowing his debt to spiral completely out of control to these astronomical levels and now must pay the price.

However, in his homily, St John Chrysostom sees that the King, in the parable, was simply issuing a stark verbal warning to bring the man to his senses and realization about the shere level of debt he is in –

For it is His purpose to alarm him by this threat, that He might bring him to supplication, not that he should [actually] be sold.

And, from the servant’s response, it is clear that he took this warning seriously. He doesn’t shrug it off or deny what has happened, but tries in some way to take responsibility for what has happened –

The servant therefore fell down, and worshipped him, saying, Lord, have patience with me, and I will pay thee all.

However, as we have already worked out, in saying this, the man must have known, must have had some sense that this would not actually be possible. He simply couldn’t guarantee that he would be able to work for another 164 years, even if he wanted to. Perhaps seeing the repentance of the man, and his clear realization as to the seriousness of his situation, the King – moved with compassion … loosed him, and forgave him the debt.

As St John asks with regards to the King: ‘Do you see again the surpassing benevolence? The servant asked only for delay and putting off the time, but He gave more than he asked, remission and forgiveness of the entire debt.’

This was a most extraordinary thing to do. Not to either demand the full amount, or at the very least, to demand the maximum which the man could realistically provide. Rather with no strings attached, and no benefit to himself whatsoever, the merciful King cancels the whole debt and releases him from this burden.

One would expect that after being saved from slavery and complete destitution, that this experience might cause a radical change in the life of this man. That he would be forever grateful to his Master and conscious of how merciful he has been to him and what a new start, a new lease of life he has been given. But, in that all too human, all too flawed and sinful way, our unloosed servant doesn’t manifest this change of heart. Instead, he searches out for someone who owed him a debt of just 100 pence, a tiny, minute fraction of the huge sum he had been absolved of, and rather than replicating the mercy of his Master, and cancelling this tiny debt, he instead thuggishly and violently demands it.

the same servant went out, and found one of his fellowservants, which owed him an hundred pence: and he laid hands on him, and took him by the throat, saying, Pay me that thou owest.

St John Chrysostom draws out attention here to the immediacy of the servant’s action.

For going out straightway, not after a long time but straightway, having the benefit fresh upon him, he abused to wickedness the gift, even the freedom bestowed on him by his master.

Note also the violence of the servant’s actions. Whereas the King made a verbal threat upon him, the unloosed servant adds physical violence to his words – ‘he laid hands on him, and took him by the throat, saying, Pay me that thou owest.

What willful forgetfulness. What a spiteful lack of mercy and compassion. In a vivid image, St John Chrysostom says that when we fail to reflect the mercy with which we have been given, we end up, ‘thrusting a sword into ourselves, revoking the sentence and the gift’. As with every sin that we commit, first and foremost we hurt ourselves, we make ourselves suffer.

Next, in a perfect mirror of his own experience, we hear the ungrateful servant’s debtor pleading before him with the same words, the very same words to the letter, with which he pleaded before his master –

And his fellowservant fell down at his feet, and besought him, saying, Have patience with me, and I will pay thee all. And he would not: but went and cast him into prison, till he should pay the debt

Whilst the King and the ungrateful servant knew that his own debt was literally unpayable, the payment of this tiny debt would have been so much more feasible and realistic, a matter of waiting but a very short period of time for this debtor to gather a few pennies, not 10, 000 talents, together.

As the Goldenmouthed says –

But he did not regard even the words by which he had been saved (for he himself on saying this was delivered from the ten thousand talents), and did not recognize so much as the harbor by which he escaped shipwreck; the gesture of supplication did not remind him of his master’s kindness, but he put away from him all these things, from covetousness and cruelty and revenge, and was more fierce than any wild beast …

And now we come to the climax of the parable, when the Good King hears of what his servant had done-

Then his lord, after that he had called him, said unto him, O thou wicked servant, I forgave thee all that debt, because thou desiredst me: Shouldest not thou also have had compassion on thy fellowservant, even as I had pity on thee? And his lord was wroth, and delivered him to the tormentors, till he should pay all that was due unto him.

As St John notes, it is here that the ungrateful servant earns his epithet of ‘wicked’ –

And whereas, when he owed ten thousand talents, he called him not wicked, neither reproached him, but showed mercy on him; when he had become harsh to his fellow-servant, then he says, O thou wicked servant.

If only he had shown just a fraction of the mercy he had been given, how much better his life would have been. What bliss would have been his. Yet the blame for his being consigned to punishment and torment, lies not with the King, nor with the servant who owed pennies, but lies solely and squarely on the shoulders of the ungrateful and wicked servant, his greed and lack of compassion.

At the very end of the parable our Lord succinctly summarises its meaning, linking back to Peter’s question as to how many times we should forgive our brother –

So likewise shall my heavenly Father do also unto you, if ye from your hearts forgive not every one his brother their trespasses.

Again, this should remind all of us of those words at the end of the Lord’s Prayer which we repeat every day and at every divine service: ‘And forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors’ or ‘forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us’. Sometimes we can become overpowered by the sins and offences, the debts of our brother. And indeed many of us have a number of people in our lives who have wounded us severely and that we are, perhaps, in different stages of trying to forgive. Let us though mediate on this parable and consider the conclusion which St John Chrysostom draws for us –

Two things therefore does He here require, both to condemn ourselves for our sins, and to forgive others; and the former for the sake of the latter, that this may become more easy (for he who considers his own sins is more indulgent to his fellow-servant); and not merely to forgive with the lips, but from the heart.

We should also remember those powerful words of the Beatitudes which we hear sung at each Divine Liturgy: ‘Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy’.

All of us our sinners, all of us have stained our pure baptismal robes and committed an untold number offences against God, against our neighbour, against our brothers and sisters. Yet despite the grieviousness of our sins, all of us have received and continue to receive the grace of absolution poured our upon us and flowing down the epitrachelion of every Orthodox priest. We have no problem, of course in forgiving and excusing ourselves, and of expecting God to always forgive us, but how cruel, how merciliess we can be towards the sins and offences of other people towards us. Let us remember the end though of this merciless and ungrateful servant and how different this all could have been if only he had shown a tiny piece of mercy.

‘But if even so it be a galling thing to you to become friends with him who has grieved you’, says St John Chrysostom, ‘to fall into hell is far more grievous; and if you had set this against that, then you would have known that to forgive is a much lighter thing’.

In the sober words of Elder Ephrem of Arizona, of blessed memory – “If you cannot forgive – forget heaven”

Dear ones, on this Afterfeast of the Transfiguration, when we recall our Saviour being lifted up on top of Mount Tabor, enshrouded in the uncreated light, let us ask for the grace of the Transfiguration to help us to forgive the sins of our brothers and sisters however grievious they may be. We must be transfigured and be lifted up from our sins and the sins committed against us. Let us see our situation not from the darkness of this world and our limited earthly perspective, but let us look down on our life from the height and light coming down to us from Mount Tabor. As ‘children of the light’, let us learn to look from a different perspective, a changed perspective a transfigured perspective seeing our own sin and our brother’s transgression in the light of eternity. May the light of Tabor illumine us all!

Amen.